I'm standing with LISC DC director Oramenta Newsome in the parking lot of a Giant in Southeast DC. It's a hot day and it's the middle of the day, but the parking lot is packed.

"If you were here 10 years ago, you would be standing in Camp Simms," a former DC National Guard training site, then a polluted brownfield. "To your left was public housing," Newsome says. "It would have been extremely deteriorated." Now, here in Congress Heights, there's a Giant--the second-largest in the city--and a shiny revamped strip mall with a bank, shoe store, and an IHOP.

"The only thing we're missing is a CVS," Newsome says.

If Newsome is a little gung-ho about Congress Heights, where her nonprofit has been investing in quality-of-life improvements since the mid-1990s, can you blame her? While the neighborhood still suffers, like much of Ward 8, from high crime and high unemployment, it does seem like Congress Heights is on the rise.

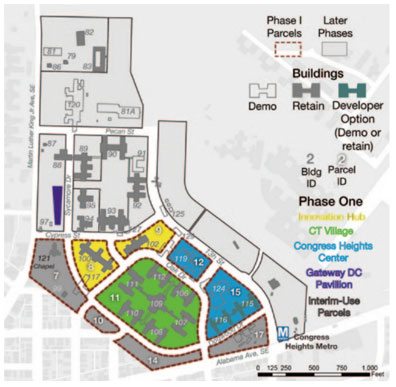

But as D.C. invests millions in new developments like the

events pavilion and

tech center at St. Elizabeths East, as Millennials begin to look east of the river for inexpensive housing, should we also be worried about the negative effects of growth?

Congress Heights isn't going to turn into 14th Street overnight. But everyone's watching to see what it

will turn into.

A balancing act

It's the same story that's played out all over the city. Neighborhoods scarred by rioting in the 1960s--neighborhoods where

dealers sold crack in broad daylight--are unrecognizable now. 14th Street, once a hotbed of drugs and prostitution, got a Whole Foods 14 years ago and the rest, as they say, is history. Formerly sleepy "streetcar suburbs" like Petworth and Brookland are now

heaven for house flippers. In other words, as everyone knows, you take the good with the bad. The decline in crime and drugs accompanies rising rents and home prices. Increased amenities--a better grocery store, a neighborhood bar or restaurant, nicer bus routes--threaten small businesses and affordable housing. It's a balancing act, and one that not many cities, D.C. included, are particularly good at.

The median rent in D.C. has

risen by 50 percent over inflation over the past ten years. One in five D.C. households--and two-thirds of the poorest households--

spend more than half their income on rent.

And in Congress Heights? "There's huge concern [about gentrification] within the residents of the area, definitely," says Evelyn Kasongo, Ward 8 Neighborhood Planning Coordinator for the Office of Planning.

Just as anywhere in D.C., some Congress Heights residents want more services and amenities, and others want to stop the tide, worried about displacement. Some want both. While it doesn't seem right now that Congress Heights could ever become a 14th Street NW, at one point 14th Street didn't seem like it could become a 14th Street.

Where we are

D.C. has some fairly progressive housing policies, according to David Bowers, vice president and market leader of nonprofit Enterprise Community Partners. "When people in other cities hear what we have," he says, like the city's housing preservation trust fund and its law that tenants must get the option to purchase their building before a landlord sells it, "people are like, 'wow.'" But, he says, "what we have is woefully inadequate to the problem."

Except in east-of-the-river communities, like Congress Heights, where apartments frequently still rent for under $1,000 (far lower than what many "affordable" buildings in other neighborhoods charge). And while some may fear gentrification, many others say that the neighborhood

needs to attract higher incomes.

"We need a mix," says Diane Benson, who's lived in Congress Heights 15 years. "It's good to have other nationalities moving in."

Residents we spoke to, with a mix of incomes, are clearheaded about their neighborhood's chances for retail. Without higher incomes, Congress Heights can't support a lot of shopping or dining options. And the current options are certainly better than what was there before, but not adequate.

"A cafe might be good," Benson says. "Healthy food, not a bunch of chicken."

The city agrees. "There's an underdeveloped market there, particularly when it comes to retail," says OP's Kasongo. OP has commissioned a retail streets study

using a toolkit it co-developed last year, it's developing a "tourbook" for retailers interested in space in the neighborhood, and the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development (DMPED) is pushing events like a monthly Whole Foods (

Whole Foods!) pop-up at the "temporary"

GATEWAY DC pavilion.

Where we're going

That pavilion is one part of the city's overall strategy for St Elizabeths East, one chunk of the former mental hospital taking up 176 acres of Congress Heights. Another part: the Rise Demonstration Center, an

$8 million renovation of a former chapel on the St. Es campus. That space is offering tech demonstrations, classes and workshops until the city can open its full tech center--which Microsoft and other big names have committed to--and begin its full-scale renovation of the campus to create a mixed-use neighborhood. (Developer teams pitching their visions for the spaces presented to the community Sept. 30, but no final decision has been made on which team will win the day.)

And over on St. Elizabeths West, the federal government still intends to move the entire Department of Homeland Security over there--eventually. That project was initially supposed to be done this year; now,

2026 is looking optimistic. The idea is that the higher incomes burning holes in DHS employees' pockets will trickle down to the surrounding community. For now, only the Coast Guard has moved in.

What if it doesn't work? What if it works too well?

A neighborhood that defies cliche

Congress Heights isn't just a neighborhood of housing projects (though there are plenty of those). Within one mile, you can go from Section 8 housing to detached homes that sell for over a half-million bucks. According to the Washington, D.C. Economic Partnership, out of the nearly 3,000 households within a half-mile of downtown Congress Heights, nearly 1 in 5 have incomes over $75,000. That's not rich by D.C. standards but it's hardly scraping by in poverty, either.

Where residents are (more or less) united is in their love of the neighborhood's relatively inexpensive housing, as well as its big yards and open spaces. In other words, there's a lot of room in Congress Heights. (There are lots of vacant lots, too. One, on a recent trip through the neighborhood, had cattails growing in it. It feels in some ways more like an exurb than a part of the nation's capital.)

With so much community support for low density, the neighborhood's development options are limited. Amenities aside, Millennials--the deep-pocketed ones that neighborhoods are trying to lure--are less likely to be attracted to such a car-dependent neighborhood.

Which brings us back to St. Elizabeths. If you can't get wealthier people to live in Congress Heights (yet), maybe you can at least get them to work and spend their money there. But so far, what with the agency's employees isolated from the community by an enormous brick wall, the economic boom has been

more of a bust. (For its part, the Coast Guard says it is trying, using local caterers and encouraging employees to volunteer with local organizations.)

And yet

"We've seen this story before in multiple neighborhoods throughout the city," says Enterprise's Bowers. "So if you live [in Congress Heights] and all you see is despair, you may not think this [gentrification] can happen again....what is the response? Don't bring in amenities? Maybe that's not the response. But let's make sure we plan for that [potential of displacement]."

LISC's Newsome agrees. "I cannot spend my time worrying about [wealthy people] going to live here. I have to worry about the janitors, the cab drivers, the cooks...I'm not naive enough to think that what I do is going to stop the tide. [But] people here have done without for so long."

And so

Natalia is a light-skinned woman who moved to Congress Heights two years ago, seeking a housing bargain. These facts alone make her a "typical" gentrifier. When I met her, she was shopping at the pop-up Whole Foods Market that sets up the first Saturday of each month at the Gateway DC pavilion.

But you know who else was shopping there? Just about everyone, of every skin color. Retired women, young professionals, everyone in between.

"I like the neighborhood as it is," Natalia says.

But, she added, "I'd love to start a cafe."

Can't get enough of this topic? Why not attend our event in two weeks--Gentrification, Revitalization, or Renaissance?--discussing affordable housing, neighborhoods in transition, and more.